While evermore appalling shenanigans within the AIG

corporation preoccupied the US media last week, I made a side trip to

the Republic of South Africa. The travails of that country are best

summed up in this song by the late pop singer Lucky Dube, who was

murdered in a botched carjacking a year and a half ago (“Remember Me”).

Daddy where ever you are remember me

In whatever you do I love you

Daddy where ever you are remember me

In whatever you do I love you

You left for the city many years ago

Promised to come back

And take care of us

Many years have gone by now

Still no sign of you Daddy

Mother died of a heart attack

Many years ago when she heard

That you were married again

Now, I’m the only one left

In the family

Chorus:

Wandering up and down

The streets of Soweto

No place to call my home

I tried to find you

Many years ago

But the women you’ re married to

was no good at all

I was in Johannesburg to give some talks at the invitation of an

architecture firm, Osmand Lange, who had designed an outstanding New

Urbanist project of some 35 acres in the otherwise Los Angeles-style

illegible suburban sprawl north of the old central business district.

The project, called Melrose Arch, was an ensemble of five-story

buildings in a set of mixed-use, dense blocks rich with good public

space — a rare thing in this otherwise ultra-fortified security state

of gated estate houses, malls, business “parks,” and freeways.

In fact, in the car coming off the very long flight from North

America, with what felt like a brain-pan full of screaming weevils

produced by jet-lag, I kept on wondering if I had somehow landed in LA

by mistake, so similar was the palm-studded terrain and most of the

objects deployed on it. After a day or so of brain rehab, the

differences became more apparent.

I spent virtually all my time there in and around Johannesburg

(“Joburg”) a world-class-sized city of nearly four million (in a

sprawling metro area of over seven million). The official race

segregation called “apartheid” was dismantled starting in 1990 by

then-President F.W. de Klerk after several decades of struggle and

resistance. With the population of about 50 million at roughly 80

percent black African, nine percent white, and the rest mostly Indian

and Malay, South Africa’s first full-suffrage national election in 1994

yielded government to the African National Congress party (ANC) led by

the long-time political prisoner Nelson Mandela. The casual observer

must assume that the choice for white South Africa at that time was

between accommodation and suicide.

A state of rather tense provisional accommodation has reigned

since then. The most conspicuous feature visible to someone from the US

was the huge numbers of black Africans everywhere, but especially those

traipsing or waiting along the the secondary highways in a country with

very poor public transit. It looked like some kind of refugee stream

from a distant war zone, but I was assured that it was just the normal

flow of daily life.

Along the same lines, the numbers of black Africans employed in

service jobs absolutely everywhere is also impressive. Every cafe,

restaurant, and commercial venue was bursting with redundant labor.

Where in the US, you might see ten employees in a given bistro, in

South Africa there were thirty. Caretakers, maids, yard-men, pool-men,

door-men, parking valets, waiters, cooks, attendants of every kind

worked constantly in the background of the still-economically dominant

white culture. Laws require the redundant hiring, and it must function

as a safety valve of income. Among these black service workers were

huge numbers of security guards posted everywhere, overseeing the

non-human security apparatus of gates, checkpoints, and electronic

entry portals that define the fortified white world.

After apartheid fell, white business fled the large central

business district of Joburg for the northern suburbs, establishing an

alternative universe of drive-in offices, malls, and gated housing

“estates” (what we call tract housing). Meanwhile, the skyscraper

district — about the size of Denver’s — was abandoned for a while.

Squatters moved into forty story towers, even after the elevators

stopped working. Other buildings were just stripped of valuables like

copper wire and fixtures. Now the downtown has been officially

reinhabited and many of the former office towers have been refitted for

apartments. But the elevators are still often broken and in 2007 a

series of rolling electric blackouts made life miserable there. I had

to wonder what the future of that place was, given how much it costs to

really maintain a skyscraper over the long haul. My guess is that the

decay must necessarily outpace the attempts at upkeep when these places

are owned, in essence, by slumlords.

On-the-ground downtown, the streets were so clogged with people

hurrying in chaotic flows along the sidewalks that the place took on

the character of an immense termite mound. I was in a car — what else?

— and was told it was not a good idea to go exploring on foot there.

Much of South Africa’s notorious crime — number one worldwide in rapes

and assaults per capita and second in murders — takes place in the

center city. There is plenty of friction, too, between South African

black nationals and black refugees from places in crisis like Zimbabwe

who sift down there by the millions and compete for income. But in the

social hierarchy, the center-city dwellers enjoy advantages less

available to the dusty township slumdwellers of distant Soweto,

southwest of the city.

Soweto was established first as a kind of barracks area for

workers in the gold and diamond mines that run in a straight line for

several hundred kilometers east-west across a geographic rift south of

the city center. The topography is visible even from a car on the

freeway, where the old gold-mine tailing heaps bigger than the pyramids

of Egypt glisten in the sun along the rift line. Another feature that

kind of defines the ambience of Soweto is the remains of the old

cyanide factory — a chemical used in processing gold ore.

Today, Soweto has grown to an aggregation of about one million

people living in various low-rise conditions ranging from vast

districts of cardboard shacks and tin-roof shanties to what have

evolved into streets of middle-class houses and even a few mansions. Up

until the fall of apartheid, the government severely limited the amount

of retail amenities that could be established in Soweto, so the

inhabitants had to travel ten miles at time to buy household goods.

Probably the weirdest thing about the life of Johannesburg and its

companion Soweto revolves around the abysmal lack of public transit.

Every day the denizens of Soweto fan out northward to work by

means of taxi-cab. A gigantic system of metered cabs and mini-vans,

many in desperate disrepair, driven with infamous recklessness, serves

the metro area’s poorest citizens. A colossal taxi “park” (parking lot

in our lingo) near the freeway entrance to Soweto’s closest-in township

dispatches all these vehicles to another massive taxi park in downtown

Joburg, with van or taxi connections at each end to take commuters

further. This exercise consumes around four hours of misery every day,

in traffic that almost always turns Joburg’s freeways into yet another

a taxi park twice a day. Returning to Soweto after a day’s work, some

people have to make two or three additional taxi connections to get

home through the sprawling townships. Many cannot afford this and the

shoulders of the connector highways off the freeway in Soweto were

filled in late afternoon with streams of people heading home on foot,

some burdened with bundles, some carrying things on their heads.

The sheer monetary expense of doing all this must be out of this

world for people with not much to begin with. Somehow, the insanity of

it has been established as “normal,” and there were few signs that the

government — now black-majority, after all — was planning to rectify

the situation. There are plans to run a new subway line across town,

but at this point it is conceived mainly as a connector to the main

airport. The South African rail system — like America’s — is

completely inadequate, and the mandatory motoring program so deeply

ingrained — and associated with the extremes of security and

fortification — that no workable consensus for getting beyond the

current situation can be formed. Otherwise, the government was getting

ready to host the World Cup of Soccer this summer and was preoccupied

with directing its planning resources to that.

The casual visitor can see a pretty clear gradient of social and

economic hierarchy in the two parallel worlds of white and black South

Africa. There is a cohort of educated urban blacks now established in

business and the bureaucracy that obviously stand above those working

in service jobs and those who are essentially bumpkins coming in from

the countryside or the “bush” or from the failing nations to the north.

Like any upper crust, the educated blacks in good jobs seal themselves

off from the lower ranks — though politically, there is a pretense to

identify with them. This black upper crust has only been in charge of

things for a decade and a half. Obviously they have not yet been able

to address problems like public transit yet, but it was unclear to me

whether all the other categories of things there, from electric power

to health services, were being managed capably.

There are as many political factions among the black majority as

there might be in any sizable nation. Friction between them sometimes

leads to violence. Corruption is not on the level of the infamous

“kleptocracies” straddling the equator, but it is far from

unknown. Right now, the nation awaits a national election coming up in

April and the near-certainty that Jacob Zuma will be elected the new

president. His ascent is widely dreaded by the white minority, who

broadly regard him as a thug.

This white minority appears to carry on with the “normal” tasks of

daily life not unlike what you would see in Europe and North America.

But close to the surface you detect a resigned fatalism. Their old

center has not held and things for them could fall apart at any time.

The evacuations of whites that occurred with the shift to

black-majority government in the 1990s have tailed down. I’m not even

sure how conscious the whites are of their own base-line nervousness,

though the multi-layered apparatus of security, with all the locks,

gates, and video cameras speaks for itself.

The combination of the fortification mentality with compulsory

motoring has left Johannesburg with a conspicuous scarcity of shared

civic space. It’s hard to beat the USA for this, but South Africa has

managed to. The architects and developers who designed the Melrose Arch

project tried to supply something that was otherwise non-existent in

the country and they did a very good job. All the classes of the

various races were present there — whites, blacks, and Asians —

sitting in the outdoor cafes, often at mixed tables, while the

virtually all-black service class puttered and watched in the

background. The nicely-scaled main square felt like the only tranquil,

open, safe public gathering place in the entire metroplex. The health

club down the street where I dropped in three times in a week reflected

the mix of races, too, as did the offices and business establishments.

Melrose Arch was a brave experiment. Its development coincided

time-wise with the more-or-less peaceful revolution out of minority

rule starting in the 1990s. There have been some copycat wannabe

spin-offs of it in other parts of the city, but nothing nearly as

successful either as an economic venture or a civic amenity.

On the whole, you got the feeling that all the multicolored upper

crusts of South Africa were largely tuned-out to some larger forces

gathering to shake up their world — in particular the energy crisis

that has moved off center-stage temporarily while banks and national

economies flounder everywhere. The energy crisis will return. South

Africa has coal and nuclear power, but not enough generating capacity

to stay very far ahead of an ongoing shortage of electric power. They

have a pretty robust coal-to-liquids program for helping to fuel all

the cars — but they also import a lot of regular oil and are at the

mercy of oil states elsewhere in Africa who resent them. The white

majority seems to ignore the fact that their future hangs by the rather

flimsy threads that hold together the combined motoring-and-security

systems that protect them. The story there is hardly over.

On the way out, I had one of those experiences that bizarrely

defines a place. I checked into the business-class lounge at the

airport only to find that no toilet was available there. They just

didn’t have any. I was sent outside down the concourse to find one.

“It’s Africa,” the old expression goes.

____________________________________?

My 2008 novel of the post-oil future, World Made By Hand, is available in paperback at all booksellers.

This blog is sponsored this week by Vaulted, an online mobile web app for investing in allocated and deliverable physical gold. To learn more visit:Kunstler.com/vaulted

|

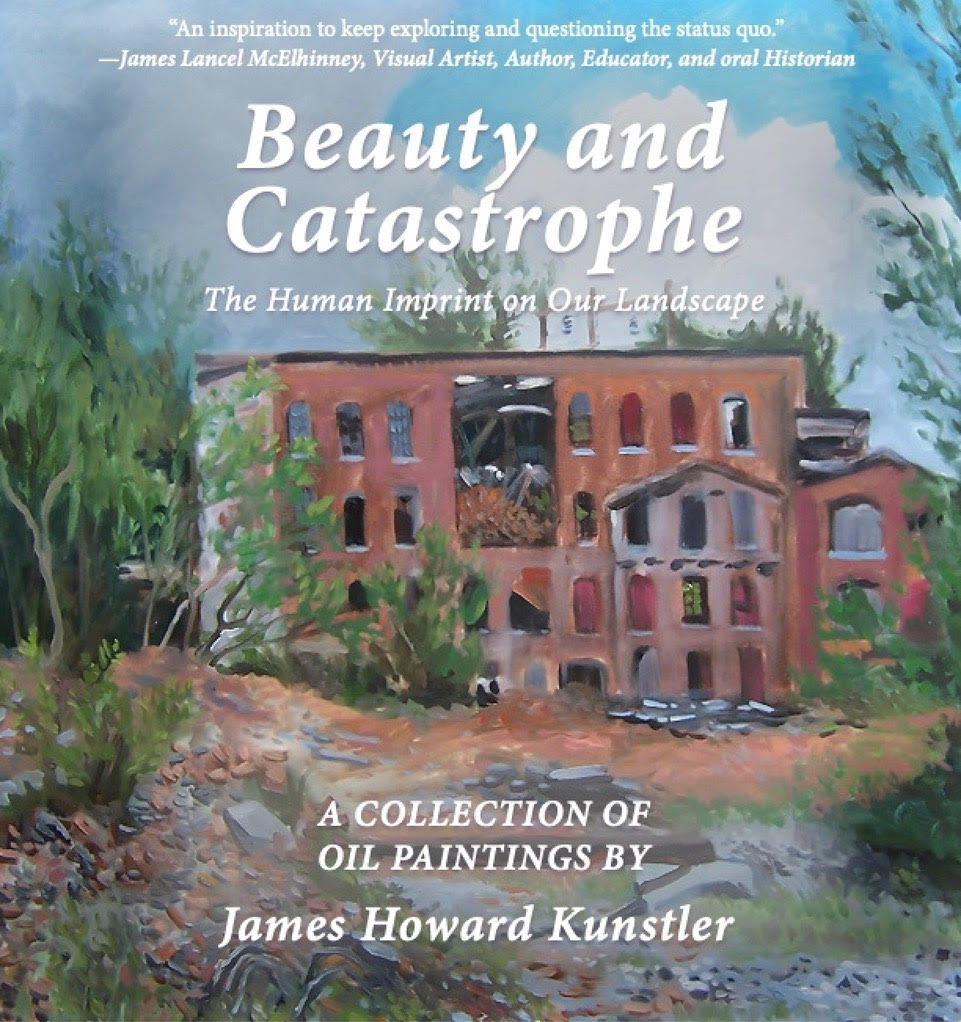

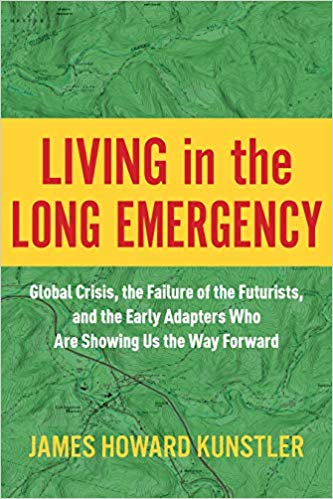

Order now! Jim’s new book Click here for signed author copies from Battenkill Books

|

Order now! Jim’s other new book |

Paintings from the 2023 Season

New Gallery 15

GET THIS BLOG VIA EMAIL PROVIDED BY SUBSTACK

You can receive Clusterfuck Nation posts in your email when you subscribe to this blog via Substack. Financial support is voluntary.

Sign up for emails via https://jameshowardkunstler.substack.com

JHK’s Three-Act Play

JHK’s Three-Act Play

For the new gamer this site so support because play minesweeper here all thing basic about this game available for the user.

You can easily see all of these and still get back to Africa the same day or choose to match them on the way to your next destination as a side trip in. Pay Someone To Take My Online Class!

Good Work

Read through ios switches here as we know there might be many who would like to learn this for one reason or another now. We can say that coursework writing service will be what we needed to go for at that time of the year. Just see that and we will like to learn it now.

Assignment Writing Ace is the right place to get top assignment writing services. They have a professional team that includes completely qualified writers who are experienced in the field of academic writing. They can give services for all types of assignments. Plagiarism-free results are 100% guaranteed as they follow the right track to complete your assignments.